In medieval times it took days, but more often weeks or months before news from elsewhere reached towns and villages. And maybe the location of Friesland, so far away for the rest of the Netherlands, was the cause of the development of a special horse breed through the centuries. Black, a proud stance, a beautiful swan neck, a small head with big eyes, a voluptuous mane and tail, fetlocks ot the legs, intelligent, friendly and with the royal trot this breed is so well known for. The Friesian Horse, named after the province it stems from and whose history is so notably parallel with that of this different part of the Netherlands. In the long history of the Friesian horse it was often famed and forgotten, but it has always stayed itself.

During the Crusades, knights used (among other horses) Friesian stallions. They were big and strong and they needed to be. Knight and harness together weighed more than 250 kilos. The road to Jerusalem was long. On the way there the necessary battles had to be won and that asked not only for endurance but also for strength and courage of the knight's horse.

Historic Notes

- Het Friesch Paard: History

- 17th Century Portrait

- Antique Friesian Postcards

- The Black Brigade

Reference

History of the Friesian

Encyclopedia

Care & Health

Historic Notes

Useful Dutch Words

Approved Stallions

Friesian Fanatics

Friesian Forum

Friesian Tales

Product Reviews

Business Reviews

Friesian Classifieds

Directories

The Friesian, as a relatively new breed in America, often frustrates those of us looking for a solid or consistent history that isn't in Dutch! Especially vague is their history before the studbook was founded, when Friesians were known by many names and were often brown! Although in no way an actual historian, I would like the Friesian's english references to be available to those interested.

Topics

Antique Friesian Postcards | The Black Brigade | Het Friesch Paard: History | 17th Century Friesian Portrait

Here is an excerpt from the history chapter of "Het Friesch Paard" by Petra van den Heuvel, translated most generously by Japke Zonneveld.

Crusaders

Early export

Even in 1276 there's notice of trade in Friesian Horses at the market in Münster (Westfalen, Germany). Friesland was Catholic in that time and held many monasteries. These had a lot of ground and it is not impossible that monks held a fair part in the horse breeding there. Plus, Friesland was part of the diocese of Münster, so the fact that Friesians were offered in Münster isn't really that strange.

Next, to the trade in Friesians to Germany until far into medieval times. They were also shipped to England. But Friesian horses travelled even further west. In April 1609 Henry Hudson sailed for the "Oost Indische Compagnie" on the ship "De Halve Maen" into the, later named after him, Hudson River. Strongholds were built in New Amsterdam (New York). The Frisian Pieter Stuyvesant was governor in the area called New Netherland between 1647 and 1664. It is a fact that Friesians were brought to New Amsterdam before 1625. From New Amsterdam they spread further over the east of America.

The Friesian horse had a large influence on the Morgan horse. The resemblance with Friesians, as well often in colour as in type and movement, is striking.

Spanish influence

Back to Europe, back to Friesland, land of the breeding. In the period between around 1300 and 1550 the Friesian horse kept its good reputation in large parts of Europe. Even through the invention of gunpowder in 1338, people kept using horses in battles in Europe. The Italian Guicciardini wrote about the Friesian that is was "beautiful and good and especially good as a warhorse." The chronicle of Dubravius tells that the Hungarian King Louis II took off to war on a black Friesian stallion on June 15, 1526.

Even though all of its power and the beloved black colour, people thought the Friesian was too heavy in the mid 16th century. And just like we have our trends now, it was in fashion then to breed a lighter, almost "modern" Friesian. This change came at the same time as the Eighty-Years War (1568-1646) between the rebellious Dutch and Spain. In those 80 years the Spanish used complete armies and many battles were fought. We [the Dutch] didn't want to be part of the almighty Spanish kingdom of King Phillips II, but form our own nation under Prince Willem van Oranje, forefather of our Queen Beatrix.

However, this war brought the greatest influence on the development of the Friesian horse in its already long history. The Spanish Dukes and army commanders rode Andalusian stallions in battle. These had been influenced by Arabian stallions in the time of the Moores. The Andalusian stallions of the Spanish "Grandes" (dukes) and generals were taken after victory in battles, also to Friesland. The stallions were used with the native mares. Even today the influence of the Andalusian and the Arabian on the Friesian is evident. Not in the colour, because that stayed mostly black, but mostly in the small head with big, brown eyes, the somewhat shaped face sometimes even with a real "Arabian dent", the swan-neck, and the elevated knee-action.

Phryso

The oldest known picture of a Friesian horse stems from 1568. Jan van der Straat made an etching of Phryso, the Friesian stallion of Don Jaun of Austria who was ruling in Naples. A copy of this picture is on the beautiful tile painting at the entrance of the Fries Paarden Centrum in Drachten [ed. note: see small picture in top left of page]. Also the monthly magazine of the KFPS, which appears since 1950, is named after this royal stallion "Phryso."

Undoubtedly, as leftover from the arts of war with horses from medieval times, riding schools were started in the 16th and 17th century. The horses in these schools had to have strong muscles and joints for training in the classical movements and jumps. Especially the levade and the courbette, jumps that were so successfully used in battle, ask enormous amounts of strength of the horse. Next to Spanish horses (forefathers of the Lippizaners, Napolitaners and Kladrubers) Friesian horses were often used. The Duke of Newcastle had a riding school in the Belgian Antwerp around 1650, and worked with Friesian stallions. Rubens student Abraham van Diepenbeeke illustrated an instructions book of the English Duke. His pictures from 1658 show us horses that look a lot like today's Friesians. The duke was pleased with the Friesian stallions in his school. "They are lighter of build (than Spanish horses) and have a greater knee-movement."

['Portrait of Pieter Schout on Horseback', Thomas de Keyser, 1660]

I ran across this while flipping through a book of artwork on Amsterdam's Rikjsmuseum. Imagine my suprise to turn the page and find a perfect example of a modern Friesian horse, painted in the 17th century! It seems the Friesian was bred in a more refined form, like that we see today, for quite some time, and the breed only started to get heavier at the beginning of the 20th century, when their use returned to primarily that of a draft horse. I should note that, while the painting seems to portray a Friesian perfectly, and I certainly believe it is one, the official description of the horse is a 'black Andalusian'. I shall let you decide for yourselves. Click on the picture for a larger view.

Here are three photos which will surely be of interest. They are from the wonderful book: Carriages of the Past; Victorian postcards of the collection of Mario Broekhuis. Published in 1998 by Wim Knijnenburg Produkties. The first thumbnail is of Alva 113 Preferant, yes, that is 113, a very early photo of an Approved Friesian stallion. He is the fifth of six approved sons by De Regent 32 Preferant, son of Prins Hendrik 24. Of the six sons, he is the only to produce approved sons of his own, two, Oom 119 and Stefanus 124.

The next two photos are also of Friesians, shown in front of the traditional Frisian sjees. Unfortunately, these photos are in a high resolution so that the text beneath them can be read, so the enlarged version may take some time for them to load properly. Click on each to see them enlarged.

This is an excerpt from a 1971 reprint of The Horse-World of London (1893) By W.J. Gordon, originally published in 1893. The book contains information about all classes of the London equine, from the coal ponies, to the stately carriage horses, to the brewsters horses, to the queen's stables. Although never using their current name, the funeral horses described in the following excerpt are with little doubt what we now know as the Friesian. The descriptions of both appearance and temperment are suprisingly similar to how they are described by adoring owners today. Also it is noted that compared to the harsh working and living conditions other horses in the book endured, the funeral horses are suprisingly well cared for and doted upon.

Update: Google now offers the entirety of this book online for viewing. You can see it, including the excerpt below, at The Horse-world of London.

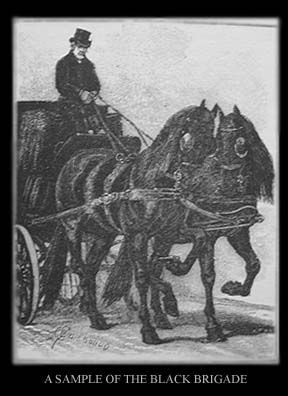

A good many of the coal horses are blacks and dark bays, and by some people they are known as "the black brigade"; but the real black brigade of London's trade are the horses used for funerals. This funeral business is a strange one in many respects, but, just as the jobmaster is in the background of the every-day working world, so the jobmaster is at the back of the burying world. The "funeral furnisher" is equal to all emergencies on account of the facilities he possesses for hiring to an almost unlimited extent, so long as the death rate is normal. The wholesale men, the "black masters," are always ready to cope with a rate of twenty per thousand - London's normal is seventeen - but when it rises above that, as it did in the influenza time, the pressure is so great that the "blacks" have to get help from the "coloured," and the "horse of pleasure" becomes familiar with the cemetery roads.

[Here I have excluded a few paragraphs concerning the Victorian funeral buisness. It is largely unrelated to the horse itself, with only a few references concerning the preference of the black Flemish horse to the regular colored horse at prestigious funerals. Although somewhat unrelated, it may be of interest and if you would like to see these paragraphs I can certainly e-mail (friesiancrazy@gmail.com) them to you or include them here upon request.]

Altogether there are about 700 of these black horses in London. They are all Flemish, and come to us from the flats of Holland and Belgium by way of Rotterdam and Harwich. They are the youngest horses we import, for they reach us when they are rising three years old, and take a year or so before they get into full swing ; in fact, they begin work as what we may call the "half-timers" of the London horse-world. when young they cost rather under than over a hundred guineas a pair, but sometimes they astray among the carriage folk, who pay for them, by mistake of course, about double the money. In about a year or more, when they have got over their sea-sickness and other ailments, and have been trained and acclimatised, they fetch 65l. each ; if they do not turn out quite good enough for first-class work they are cleared out to the second-class men at about twenty-five guineas ; if they go to the repository they average 10l. ; if they go to the knacker's they average thirty-five shillings, and they generally go there after six years work. Most of them are stallions, for Flemish geldings go shabby and brown. They are cheaper now than they were a year or two back, for the ubiquitous American took to buying them in their native land for importation to the States, and thereby sent up the price ; but the law of supply and demand came into check the rise, and some enterprising individual actually took to importing black horses here from the States, and so spoilt the corner.

Here, in the East Road, are about eighty genuine Flemings, housed in capital stables, well built, lofty, light, and well ventilated, all on the ground floor. Over every horse is his name, every horse being named from the celebrity, ancient or modern, most talked about at the time of his purchase, a system which has a somewhat comical side when the horses come to be worked together. Some curious traits of character are revealed among these celebrities as we pay our call at their several stalls. General Booth, for instance, is "most amiable, and will work with any horse in the stud" ; all the Salvationists "are doing well," except Railton, "who is showing too much blood and fire. Last week he had a plume put on his head for the first time, and that upset him." Stead, according to his keeper, is "a good horse, a capital horse - showy perhaps, but some people like the showy ; he does a lot of work, and fancies he does more than he does. We are trying him with General Booth, but he will soon tire him out, as he has done others. He wouldn't work with Huxley at any price!" Curiously enough, Huxley "will not work with Tyndall, but gets on capitally with Dr. Barnardo." Tyndall, on the other hand, "goes well with Dickens," but has a decided aversion to Henry Ward Beecher. Morley works comfortably with Balfour, but Harcourt and Davitt won't do as a pair anyhow." An ideal team seems to consist of Bradlaugh, John Knox, Dr. Adler and Cardinal Manning. But the practice of naming horses after church and chapel dignitaries is being dropped owing to a superstition of the stable. "All the horses," the horsekeeper says, "named after that kind of person go wrong somehow!" And so we leave Canon Farrar, and Canon Liddon, and Dr. Punshon, and John Wesley and other lesser lights to glance a the empty stalls of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, now "out on a job," and meet in turn with Sequah and Pasteur, Mesmer and Mattei. Then we find ourselves amid a bewildering mixture of poets, politicians, artists, actors, and musicians.

"Why don't you sort them out into stables, and have a poet stable, and artist stable, and so on?"

"They never would stand quiet. The poets would never agree ; and as to the politicians - well, you know what politicians are, and these namesakes of theirs are as like them as two peas!" And so the horses after they are named have to be changed about until they find fit companions, and then everything goes harmoniously. The stud is worked in sections of four ; every man has four horses which he looks after and drives ; under him being another man, who drives when the horses go out in pairs instead of in the team.

One would think these horses were big, black retriever dogs, to judge by the liking and understanding which spring up between them and their masters. It is astonishing what a lovable, intelligent animal a horse is when he finds he is understood. According to popular report these Flemish stallions are the most vicious and ill-tempered of brutes ; but those who keep them and know them are of the very opposite opinion.

"I am not a horsey man," said Mr. Dottridge to us, "but I have known this one particular class of horse all my life, and I say they are quite affectionate and good-natured, and seem to know instinctively what you say to them and what you want. If you treat them well they will treat you well. One thing they have is an immense amount of self-esteem, and that you have to humour. Of course I have to choose the horses, and I do not choose the vicious ones. I can tell them by the peculiar glance they give as they look round at me. the whole manner of the horse, like the whole manner of a man, betrays his character. Even his nose will tell you. People make fun of Roman noses ; now I never knew a horse with a Roman nose to be ill-natured. The horse must feel that your will is stronger than his, and he does feel it instinctively. He knows at once if a man is afraid of him or even nervous, and no man in that state will ever do any good with a horse. Even when you are driving, if you begin to get nervous, the horse knows it instantly. He is in communication with you by means of the rein, and he is somehow sensible of the change in your mind, although perhaps you are hardly conscious of it. I have no doubt whatever but that you can influence a horse even when he is ill, by mere power of will. There are affinities between a man and a horse which are at present inexplicable, but they exist all the same."

There is an old joke about the costermonger's donkey who looked so miserable because he had been standing for a week between two hearse horses, and had not got over the depression. The reply to this is that the depression is mutual. The "black family" has always to be alone ; if a coloured horse is stood in one of the stalls, the rest of the horses in the stable will at once become miserable and fretful. The experiment has been tried over and over again, and always with the same result ; and thus it has com about that in the black master's yards, the coloured horses used for ordinary draught work are always in a stable by themselves.

The funeral horse hardly needs description. the breed has been the same for centuries. He stands about sixteen hands, and weighs between 12 and 13 cwt. The weight behind him is not excessive, for the car does not weigh over 17 cwt., and even with a lead coffin he has the lightest load of any of our draught horses. The worst roads he travels are the hilly ones of Highgate, Finchley, and Norwood. These he knows well and does not appreciate. In a few months he gets to recognise all the cemetery roads "like a book," and after he is out of the bye streets he wants practically no driving, as he goes by himself, taking all the proper corners and making all the proper pauses. This knowledge of the road has its inconveniences, as it is often difficult to get him past the familiar corner when he is out at exercise. But of late he has had exercise enough at work, and during the influenza epidemic was doing his three and four trips a day, and the funerals had to take place not to suit the convenience of the relatives, but the available horse-power of the undertaker. Six days a week he works, for after a long agitation there are now no London funerals on Sundays, except perhaps those of the Jews, for which the horses have their day?s rest in the week.

To feed such a horse costs perhaps two shillings a day - it is a trifle under that, over the 700 - and his food differs from that of any other London horse. In his native Flanders he is fed a good deal upon slops, soups, mashes and so forth ; and as Scotsman does best on his oatmeal, so the funeral horse, to keep in condition, must have the rye-bread of his youth. Rye-bread, oats and hay form his mixture, with perhaps a little clover, but not much, for this would not do to heat him, and beans and such things are absolutely forbidden. Every Saturday he has a mash like other horses, but unlike them his mash consists, not of bran alone, but of bran and linseed in equal quantities. What the linseed is for we know not ; it may be, as a Life Guardsman suggested to us, to make his hair glossy, that beautiful silky hair which is at once his pride and the reason of his special employment, and the sign of his delicate, sensitive constitution.

[The Horse World of London (1893) by W.J. Gordon; Chapter XI, 'The Black Brigade'; pages 138-147]